Threads & Fragments:

The Scrapbooks

of Jean Kingsnorth

1933–2023

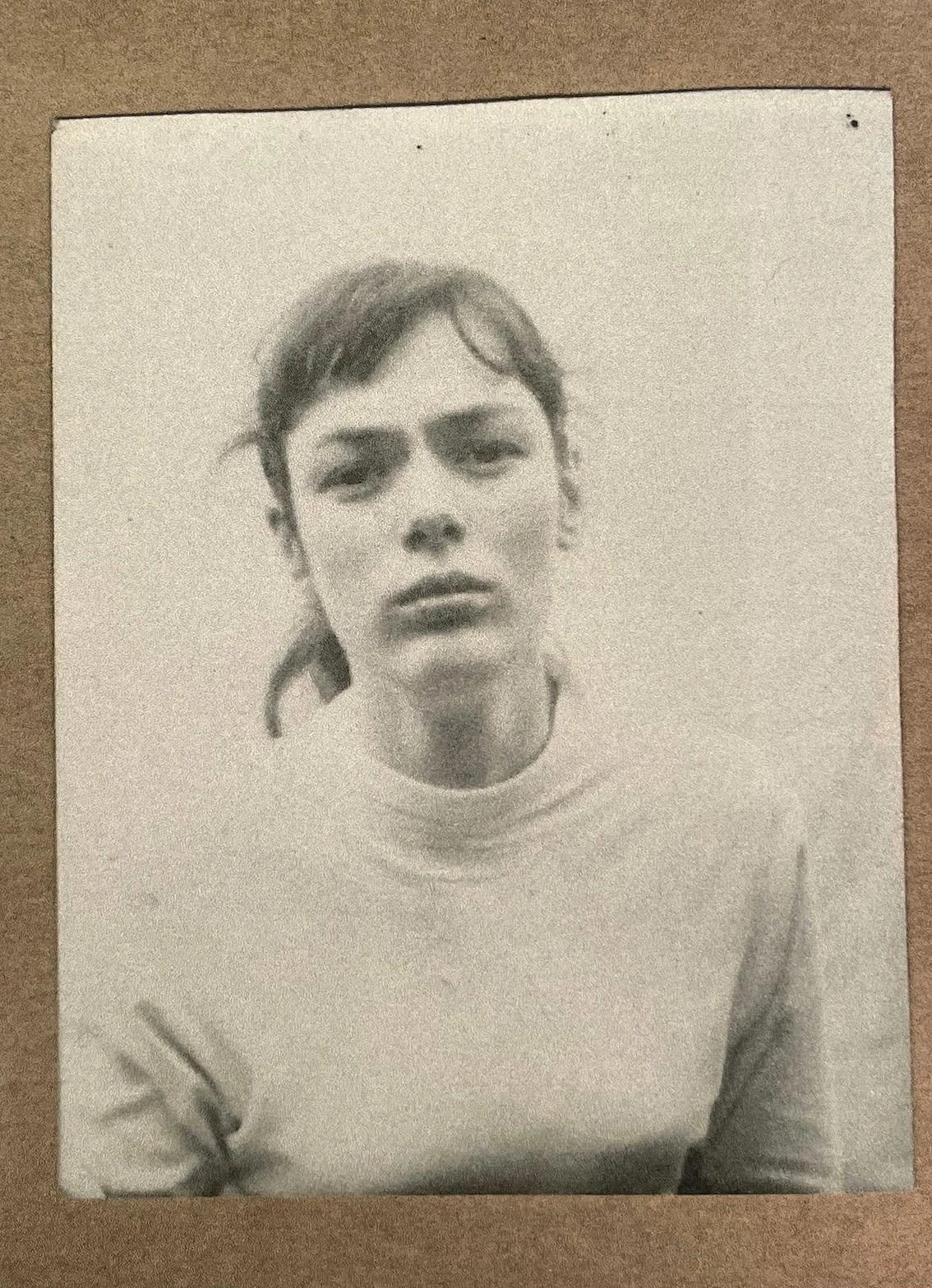

Jean Kingsnorth in the 1950s. Courtesy of the artist’s family.

Unlike conventional scrapbooks, the original function of which was the storage of memories, the artist’s scrapbook is more akin to an archive; a hybrid object incorporating the characteristics of journals, photo albums, sketchbooks and zines; a precious cache of half-born visual ideas sewn together with fragments of stories which may or may not grow to be more fully formed; a recording of thoughts, but also of things. These thing-thoughts offer a glimpse into the processes that precede making; the informal gathering of material that comes before formal execution.

Jean Kingsnorth was born in 1933 in Kent, South East England, where the wild flower meadows of The High Weald made a significant impression on her as a young artist. Working predominantly with paper and textiles, Jean’s long artistic career spanned more than half a century. Throughout her scrapbooks and her paper and textile works, Jean explored the visual and metaphoric potential of Greek myths, specifically the figure of Medea from the Ancient Greek tragedy by Euripides who is betrayed and abandoned by her husband. Her works were exhibited in group and solo shows throughout the UK during her lifetime but this is the first time Jean’s scrapbooks have been seen outside her studio.

Born into a family of botanical flower painters from New Zealand, Jean was taught how to paint by her grandmother from a young age. Her early landscapes were informed by a flight from England to France in a Douglas C47 Dakota, immediately after which she painted her first abstract landscapes. After graduating from The Courtauld Institute of Art Jean established herself as a freelance art writer and Italian translator before completing postgraduate studies at Goldsmiths where she focused on textiles and began introducing stitching into works on paper. Following two years as an assistant to the theatrical costume designer Aubrey Samuel between 1955 and 1957, Jean lectured in art history at various institutions throughout the 60s and 70s including South East Essex College, North East London Polytechnic and the Chelsea School of Art, before dedicating herself to her own work full-time in the late 1970s.

Jean’s first solo exhibitions were held at the Drew Gallery in Canterbury directed by the Australian-born curator Sandra Drew who, ‘[from her kitchen table in Canterbury […] quietly reinvented the exhibition format.” (1) Drew’s ambitious and ground-breaking exhibition program throughout the 80s and 90s, which focused on nurturing female emerging artists–including Phyllida Barlow and Rose Finn-Kelcey–has left an important and lasting legacy. Sandra Drew presented two exhibitions of Jean’s work in Canterbury, the first in 1987 and the second in 1993, both of which were informed by the story of Jason and the Argonauts and Medea’s challenges to the gender and social norms of her time.

Jean’s scrapbooks were created alongside her paperworks over the course of several decades. They provide a unique insight into her artistic process; her creative intimacy with images, her skill in composition, her sensitivity for form and colour, her fascination with archaeology and the Argonaut voyage, and above all her identification with the powerful figure of Medea. As research and development documents their pages show a variety of approaches to dealing with the framing device of the page and record her visual obsessions in a clatter of voices and references. As objects they are fascinating. Each is its own world. A list of elements on a single page might include, newspaper and magazine clippings, fragments of advertisements, images of ancient and modern sculpture, Near and Far-Eastern artefacts, Greek and Italian archaeological remains, verdigris and rust, textile fragments, Mediaeval furniture, landscapes, wildlife, images of plants and trees, maps, and movie stills. One of Jean’s earliest scrapbooks is dedicated entirely to Medea using Pasolini’s 1969 film as a starting point. In others she makes only brief appearances, but her presence is always felt.

In my view, it is through Medea that Jean’s work speaks to the rights of women and the injustices experienced by women and girls in patriarchal societies across milenia. Her voice speaks loudest in the scrapbook entitled “The voyage of the Argo”, which opens with the striking image of Maria Callas as Pasolini’s Medea pointing the way; not forward or into the book, but behind her, complicating the continuity of the narrative. As Barbara W. Boyd has written, Medea understands “that the continuity promised by epic ideology can only be destructive to her, and that the solution, therefore, lies not in maintaining continuity, but in destroying it.” (2) The nature of the scrapbook is similarly discontinuous in its constant gathering up of fragments of the material world and its refusal to be finished or defined.

Medea’s refusal to be defined has aligned her with feminist discourse since at least the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Her story was adopted by the suffragette movement in Victorian Britain coinciding with public debates about divorce laws and the growing freedoms of women in England. For example the poet, Amy Levy’s “Medea: A Dramatic Fragment” (1881), uses the format of the closet drama to reveal a patriarchal culture that rejects Medea long before her husband’s actions lead her to murder and filicide.(3) Women poets like Levy and her contemporary Augusta Webster (1837-1894), reworked Euripides’ text to create a version of Medea that related to the challenges they faced in their own lives; specifically how rigid cultural expectations such as marriage, and motherhood can destroy a woman’s sense of self.

Medea experienced renewed interest during the Second Wave Feminist Movement in the 1960s and 70s, being interpreted as a woman’s struggle to take charge of her own life in a male-dominated world. At that same time, in the wake of the Women’s Liberation Movement, feminist artists in particular sought to resurrect women’s craft and decorative arts such as embroidery, weaving and paper making, as mediums through which to express female experience. This re-engagement with natural materials was connected to Medieval women’s crafts such as midwifery and herbal medicine which were labelled as “witchcraft” and abolished in order to control and subvert women’s work. Jean discussed magic and ritual in written statements about her work, particularly in relation to Medea, whose spells and herb-magic allowed her husband, Jason to acquire the mythic Golden Fleece. The process-oriented approach to scrapbooks aligns them closely with the idea of “thinking-through-making” associated with this craft-based Second Wave Feminist work. Is it too much then to call them spell books?

As Ellen Gruber Garvey has written, “[w]hat makes scrapbooks so alluring is exactly what makes them hard to define and write about in a general sense. But what a scrapbook can do is reveal collective culture, and how its maker engaged with it. Each is a unique act of remediation between that individual and the world in expressing a particular creative intimacy with images that can be hard to articulate.”(4)

The same is true of Jean Kingsnorth’s scrapbooks; but as Jean herself once said of her own work, “I like dangling threads.”(5)

1.Philomena Epps, “The Overlooked Legacy of Sandra Drew”, Frieze, Issue 205, June 2019

2. Barbara W. Boyd, “Nescioquid maius: Gender, Genre, and the Repetitions of Ovid’s Medea,” Dictynna [Online], 16 | 2019, posted online on December 18, 2019, consulted on July 4, 2024. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/dictynna/1962; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/dictynna.1962

3. A play intended to be but read by a solitary reader as opposed to performed on stage to an audience

4. Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 14.

5. Jean Kingsnorth in an interview with Stantons Coffee House, July 4, 2018